- Home

- Sally van Gent

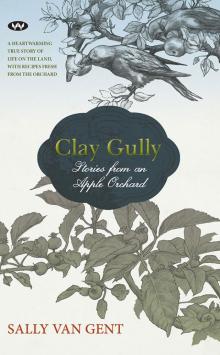

Clay Gully

Clay Gully Read online

Wakefield Press

CLAY GULLY

Sally van Gent lives in a forest near Bendigo with her husband

and their many demanding dogs, fish, tame magpies and

visiting kangaroos.

Sally was born in England, where she trained as a teacher

at Bretton Hall College for Music, Art and Drama. She

has lived in many countries, including Qatar, Abu Dhabi,

Kuwait, Mauritius and Singapore, and has been a longtime

birdwatcher and field naturalist. Sally survived breast cancer—

helped, she believes, by her affinity with nature.

Wakefield Press

16 Rose Street

Mile End

South Australia 5031

www.wakefieldpress.com.au

First published 2013

Reprinted 2014 (twice), 2018

This edition published 2018

Copyright © Sally van Gent, 2013

All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes

of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no

part may be reproduced without written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the

publisher.

Edited by Julia Beaven, Wakefield Press

Cover designed by Stacey Zass, page 12

Illustrated by Sally van Gent

ISBN 978 1 74305 190 0

For my grandchildren

Edward, Rose and Ari,

Ben and James.

Contents

PART ONE

Turning the Soil

PART TWO

Bramleys, Bees and Button Quail

PART THREE

Drought

Acknowledgements

Recipe Index

PART ONE

Turning the Soil

After several months of fruitless searching around Bendigo in central Victoria, the agent calls to tell us he has found our perfect home. Apparently the house is in the middle of ten acres of bush and farmland. Right away I know we can’t afford a property like that. The agent insists I at least drive past the place.

He tells me, ‘If you wait a bit the price will come down. I’ve heard the owners are about to go bankrupt.’

How would you like to pay this man to sell your house, I wonder.

Out of curiosity I drive down the winding dirt road. To the left are green paddocks where a horse is grazing. On the other side there is forest, all the way down the hill. At the bottom, where there is a wide curve in the road, I spot the house through the gum trees. It stands in the centre of a lightly treed paddock and to the side is open bush land. The agent persuades us to have a look inside. The house, though adequate, is unimpressive. It has a dingy seventies-style kitchen and worse, there is ghastly brown and cream shag-pile carpet almost everywhere. I look at the view through the living-room window and I don’t care.

It’s been a wet spring and water cascades over the paddocks, draining from the bush higher up the hill. The agent sends us off to walk around the property unaccompanied as he doesn’t want to get his feet soaked. Above the house the gum trees lean out over two dams. Up here the rich soil of the paddocks gives way to stony ground, and a patchwork of wildflowers grows between the grey, lichen-coated boulders.

Three months later we receive another call from the agent. ‘The owners have gone broke, are you still interested in the house?’

Yes, definitely.

I walk into the back garden the first morning after we have moved in and confront a scene straight from the classic Hitchcock horror movie, The Birds. Along the top of the fence a row of strange, black birds with hooked beaks stare down at me through glowing red eyes. They don’t attempt to fly away when I move towards them. Instead they begin to rock back and forth in unison, all the time letting out weird, breathy whistles. When they finally fly off I see they have white wing feathers.

Beside the house there’s a large shed with an earth floor where the previous owners conducted their business of making concrete garden ornaments. A giraffe with a broken neck sits near the side gate and on the back verandah there’s a whole farmyard of concrete chickens, ducks and small animals. My mother, who lives in a nearby retirement village, suggests the elderly people there might like them. Soon the animals have all found new homes and one old man, who’s been a farmer all his life, is absolutely delighted to have chickens and ducks in his backyard again.

At night a dozen large spiders with red-striped legs construct huge webs across the verandah. They catch a multitude of tiny moths, attracted by the kitchen light. These same moths provide a welcome dinner for two small frogs lying in wait on the window.

The front of the property is divided by a broad irrigation channel, used to flood the paddocks in the days when they were part of a dairy farm. Contemplating the grassy, treeless area farthest from the house, we discuss its possible uses. In this, our first year at Clay Gully, our dams fill with water in the spring and thunderstorms replenish them in the summer. Good rains are predicted for next year offering us the opportunity to establish an agricultural enterprise. I think of goats and chickens but my husband, Nick, vetoes all my suggestions. He knows only too well that I can’t kill anything and is already anticipating the vet bills involved in keeping alive aging hens, well past their egg-laying days.

A lover of good wine, his thoughts turn naturally to planting a vineyard, but I can see problems with this suggestion. Not having the necessary knowledge or equipment to process the grapes ourselves, we would be dependent on large wineries to take our fruit and set the price. Instead I think of the beautiful apples my grandfather grew in England—Bramley’s Seedling, Lord Lambourne and Red Astrachan. There must be a market for these delicious, forgotten varieties. My grandfather grew them without artificial fertilisers or pesticides. We decide to follow the long path leading to full organic certification of the orchard.

It’s necessary to have a third dam dug in front of the house and to purchase additional rural water. The contractor isn’t pleased with me when I insist on having an island in the middle of the dam. It makes his job more difficult but I know it’ll look beautiful and will be a refuge for water birds.

Then we discover Badgers Keep, a wonderful heritage apple nursery with over 500 different cultivars. With so many to choose from, I spend many hours poring over their descriptions. One apple we should definitely grow is the Bramley’s Seedling. The population of the UK eats millions of Bramleys every year and I’m convinced that once Australians try them they will love them too. The variety has stood the test of time. The original tree, growing in a garden in Nottinghamshire, is still bearing fruit after 200 years.

Next I select Autumn Pearmain, striped and perfumed, and grown since the late 1500s. Then there is the Orleans Reinette, yellow, sweet and nutty, and the soft and juicy Beauty of Bath. My husband Nick, being Dutch, has his own favourite apple much loved on the continent. This is the Belle de Boskoop, sometimes known as Goudreinet. It has a strong flavour making it excellent for cooking. If left longer on the tree it turns into a fragrant, soft-pink dessert apple. We order the Bramley’s Seedling and Belle de Boskoop and by the time we’ve selected enough cultivars for their pollination, we have twenty-four different varieties. In all there will be 300 trees.

For every tree there needs to be another which flowers at the same time, since apples are not normally self-fertile. There’s a particular problem with both the Bramleys and Belle de Boskoop. They are triploid varieties, meaning their pollen is too weak to fertilise other trees. Therefore we must plant two pollinators together so they can impregnate each other as well as the Bramleys and Belles.

Nick, who was a marine engineer, prepares an

amazing array of pumps and pipes. They can move the water from the three dams to wherever it’s needed on the block. He draws me a diagram that I follow when I’m watering, but the system is so complex I feel as if I need marine training too.

As my husband’s other business becomes increasingly demanding, I find myself left with full responsibility for the orchard. Rightly described by Nick as a technical moron, I need to learn how to drive a tractor, cope with the irrigation system and become efficient with spray equipment. Fortunately he comes to my rescue when everything goes wrong, machinery breaks down or the pipes belch out water.

We decide to plant the orchard in stages, putting in 100 trees each year. This will allow enough time for us to prepare the land and for Clive and Margaret at Badgers Keep to graft the trees.

Behind the house the hillside is rocky with only a thin layer of soil; the pearly quartz is near the surface here. Although there’s never been mining on our property, this white rock carries gold and the signs of digging and sluicing can be seen all through the surrounding bush. In some places in the forest there are hidden shafts, long since abandoned. It’s best to keep to one of the many tracks left by the goldminers when you walk there.

Over the years rainwater has carried the soil from the hill and deposited it in the paddocks below the house, and here it’s rich and deep. Our main concern at planting time is to ensure the trees don’t get wet feet when rainwater floods down the hillside in the winter. For that reason we decide to plant them on raised beds.

The extra water needed for the trees is to be delivered through a water race. It runs for many kilometres through the bush, servicing farms and villages along the way. After the bailiff opens the gate in the race, the water takes a whole day to run down the hill into our dam. Along the way it dislodges fallen leaves and branches. For the first two days we need to be ready with a spade to remove any blockages before the water overflows into the adjoining paddocks.

The spring rains continue and I decide to take advantage of them. Along the side of the orchard I dig in a row of native plants: bottlebrushes with fluffy red flowers, pale yellow melaleucas and purple kunzeas. In between I add a few small ornamental gum trees with curly grey, overlapping leaves. Hopefully these plants will encourage useful predatory insects to settle in the orchard and protect the apple trees.

Between the rows of apples I scatter subterranean clover seed which soon forms a thick green carpet. Although it dies back in the summer heat, it reappears when the rains return in the autumn. The nectar-rich flowers attract the bees and the roots improve the soil.

We plant a mixed orchard in front of the house. There are apricots, pears, greengage plums and a loquat tree. When the pistachios split open I bake them in the oven on beds of salt. After a while there are big bowls of red cherries to put on the table at Christmas.

I buy two olive trees from a Greek farmer at the market. He gives me a funny look when in my ignorance I ask him for black olive trees, not realising that olives change colour as they ripen. Italian friends show me how to cure the green ones, and some I leave to swell and turn shiny black. We serve them with drinks, sliced on pizzas and in a tuna tart. At the end of summer I pick the quinces and make a deep amber quince paste.

Quince Paste

When I make this the whole house fills with the delicate smell of the fruit. I don’t recommend cooking too many quinces at a time because of the amount of stirring involved.

quinces

white sugar

Wash the quinces and wipe off the fur. Place them on a baking sheet. Roast in a slow oven until soft. Allow to cool. Then take out the cores and carefully remove any remaining seeds or stalk, but leave the skin on. Use a blender to turn the flesh into a smooth paste. Weigh it and measure out half that amount in white sugar. Combine the sugar and quince and stir well.

Put the mixture into a heavy bottomed pan and cook over a low heat. Stir frequently, especially towards the end of cooking to prevent burning. Depending on the quantity, this may take 2 hours or more.

When the mixture is very thick and pulls away from the sides and bottom of the pan, remove from the heat. Spread the mixture onto a baking tray lined with nonstick paper.

Slice and serve with cheese or dust with icing sugar and serve as a sweet.

Orange Pistachio Biscuits

These are thin, crisp biscuits with a delicate balance between the orange, pistachio and cardamom flavours.

160 grams unsalted pistachios

¾ cup caster sugar

1 egg, lightly beaten

1 heaped tablespoon self-raising flour

3 heaped teaspoons grated orange rind

1 level teaspoon ground cardamom

Pre-heat the oven to 160°C (or 150°C if fan forced). Line a baking tray with non-stick paper.

Halve or roughly chop 30 grams of the pistachios. Coarsely grind the remaining 130 grams in a food processer. Add the flour, sugar and other ingredients and stir well.

Place teaspoons of the mixture onto the tray 4 centimetres apart. Stud with the pistachio pieces and bake for approximately 10 minutes or until edges brown. Allow to cool before lifting onto a wire rack.

Olive and Tuna Tart

The strong taste of the olives and anchovies nicely contrasts with the blander tuna filling.

23 centimetre shortcrust pastry case

40 grams cornflour

400 millilitres milk

knob of butter

425 g can tuna in brine or spring water

¼ cup finely chopped parsley

1 tablespoon lemon juice

salt and pepper

45 grams anchovy fillets

1 ripe tomato

80 grams pitted olives (home grown, or for a decorative effect, red pimento stuffed)

lemon slice

Preheat the oven to 180°C. Prick the base of the flan case with a fork and bake blind for approximately 15 minutes. (Either cover the base with paper and baking beans or with pieces of crumpled foil.) Remove the foil/beans 5 minutes before the end of cooking. When lightly browned remove the case from the oven and allow to cool.

Dissolve the cornflour in 100 millilitres of the milk. Gently heat the remainder of the milk with a knob of butter. When almost boiling remove the pan from the heat and add the cornflour mixture stirring rapidly. Return to the stove and cook over a low heat continuing to stir until the sauce is smooth and thick. Remove from the heat.

Drain the tuna and place it in a bowl with the chopped parsley, lemon juice and salt and pepper. Stir in the white sauce.

When cool turn the mixture into the flan case. Lay the anchovies on top like the spokes of a wheel. Halve the tomato and place a thin slice between each anchovy. Cut the olives in half and place cut side up all around the edge of the tart and wherever else there is a space. Arrange a slice of lemon in the centre.

This is better if allowed to go cold and set in the fridge. Reheat next day in the oven or serve cold if preferred.

My elder son finds a chihuahua, which he names Stijl, wandering amongst the traffic on Lygon Street in Melbourne. He is the tiniest dog I have ever seen. It appears he has some sort of problem, for the tip of his tongue peeps permanently from the corner of his mouth. After a while Angus, who is still a student, is unable to keep him and so Stijl comes to live with us.

When friends visit they start to say, ‘What a dear little …’ but trail off when they see what is hanging underneath, for his penis is so long that it skims the floor. This may not have mattered when he lived in the city, but here the dust and dirt in the bush make him constantly sore. The vet tries medication and castration but to no avail. Finally we face the inevitable. At least half of it must be cut off. I am filled with guilt at putting him through such a dreadful operation, but within a couple of days he is fine and running through the bush with the other dogs.

I don’t know how old he is but he has few teeth and there is white hair around his muzzle. When, after a few years, he dies suddenly from a heart atta

ck I am devastated. My husband, concerned, goes to Melbourne and returns with a chihuahua pup. This one is jet black. I ask Nick what the parents were like, but he hasn’t seen them. After a few weeks the puppy grows a small grey beard and I know something is wrong. Shortly afterwards the spindly legs suddenly sprout and he looks like a chihuahua on stilts. When I open the door he circles the paddock, running so fast I can only make out a black blur. This is no chihuahua. Still, we come to love this sweet, quiet dog. We call him Reuben. He is my shadow.

Although I love Reuben dearly, I still miss Stijl and long for another chihuahua. After some persuasion Nick gives in and we adopt a third dog, a companion for Reuben and our German shorthaired pointer, Coby.

He is a little grey-coated fellow with white bib and paws. We check his parents to make sure this one is indeed a chihuahua. Typical of his breed, José is all front and false courage. Despite his size he soon has our other dogs under control. He makes himself useful by immediately assuming the role of guard dog, and warning us of approaching strangers.

Soon after moving in, I discover a narrow path leading up the hill beyond our house to a large dam hidden in the bush. It’s quite beautiful, and is an ideal place for the dogs to have a walk or swim. I take them up there every morning before I go to work and, as usual, our shorthaired pointer vanishes into the bush in search of rabbits. I let her go, since she always reappears just as I return to our gate. For company I have my chihuahua, José, but today he’s slow and lags behind. When I realise he isn’t following me I turn back in time to see a magpie watching him closely from a bough of yellow wattle. Suddenly the bird flies down and struts purposefully towards the dog, now standing frozen on the path. I have visions of what a big sharp beak could do to a tiny chihuahua, and quickly scoop him out of harm’s way before continuing my walk.

Clay Gully

Clay Gully